Joe Charrington is a Sussex-based photographer whose work deals with the deep connections between people and place. His most recent photo book, Dumnonia explores how humans have interacted with the Dartmoor landscape from the Bronze Age to the present day.

The Collective’s Jon Vernon spoke to Joe to discuss his relationship with the moor, and how spending time in such places informs his photographic practice.

Some of the most fascinating interviews we’ve done for the Dartmoor Collective website over the years have been where we’ve explored how the moor has inspired artists from outside its immediate area, and how their responses to the landscape are often quite different to those of us who live and work here full time.

As an artist usually based in East Sussex, can you give us an insight into your own relationship with Dartmoor, what brought you to the moor, and the impact it has had on your creative practice?

That’s a very interesting question. I am based in East Sussex, from the seaside town of Hastings to be exact and it’s an area where you find yourself confronted with history whenever you step outside the door. Road names, businesses, parks…its “1066 this” or “Senlac that”. There’s even a tradesman that trades under the self donned title of “William the Concreter” who I finally got to pass along a wooded backroad the other day – you can imagine my glee as I peered out of the car window…Royalty. But to bring it around to Dartmoor, I’ve found myself increasingly fascinated where these remnants of the past find their way into the present day. It’s in this collaborative topography that my focus is drawn and over the past two years I’ve been meaning to get out of Sussex and explore some more places that have been lurking in the edgelands of my mind.

I’ve had my eye on Dartmoor for a while and when I saw Mayes Creative offered a residency program down there I jumped at the opportunity and applied and a few months later I found myself wandering out onto the moor from Postbridge with a large format camera.

Dartmoor has always been this unknown spectre in the maps of my mind, so it was quite surreal to experience it. With my work I’m also always looking for a narrative, something interesting to underpin the work, and I really felt like I’d find that in Dartmoor.

I’d also been speaking to Fraser from Bracken Books, the bookmaker and publisher that published my first book Beneath Mercia last year. We’d spoken about doing another book and when this all came together with my plans to come down to Dartmoor to make this work and it all kind of just clicked into place. I think it changed the way I made work – imagining them on a page instead of a website or phone.

Dartmoor has been described as a “palimpsest landscape” – a place where the layers of past use of the land and it’s rituals and traditions are never far from the surface. There seems to be a thread of similar landscapes running through your work.

What is it that draws you to such landscapes, and what parallels and differences have you found between Dartmoor and other places which have featured in your work?

This is a nice segue from where I left off with your last question, I really enjoy that word “Palimpsest” – even the construction of the word feels like a gesture backwards. I’ve sort of answered that first part within my last answer but it’s not just the landscape, I’ve been quite enjoying this strand of sociocultural anthropology that looks at the identity of people along with places and their function. I suppose that’s what I’m looking for in a place, this conversation between the entire history of people and the entire history of the landscape.

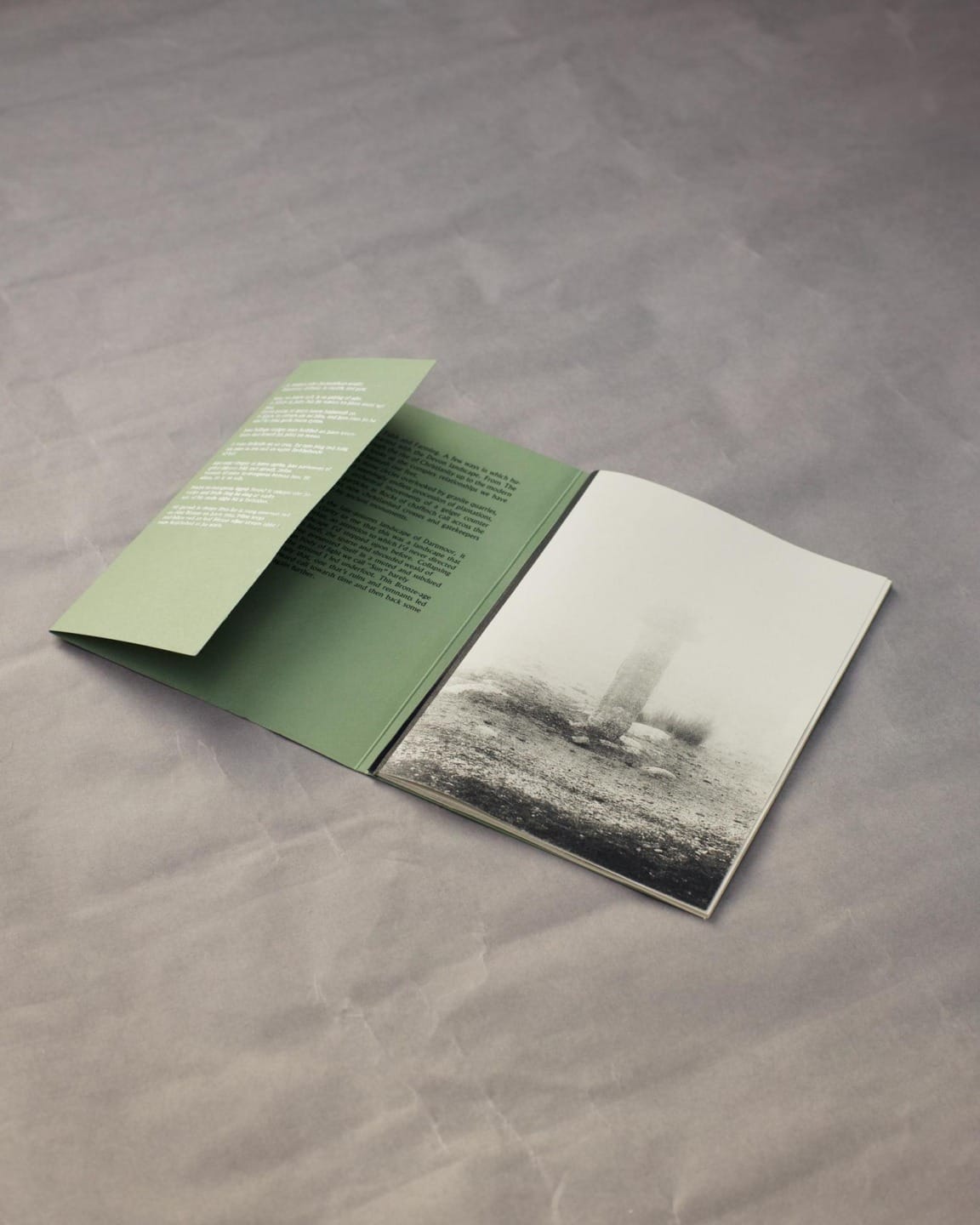

You could picture it sort of like a loom, with all these threads interacting with one another at different points. It goes two ways you know – the act of making something like a menhir, building or any mark on the landscape is as much a conversation forward in time as it is backward in time for the people like us experiencing it now.

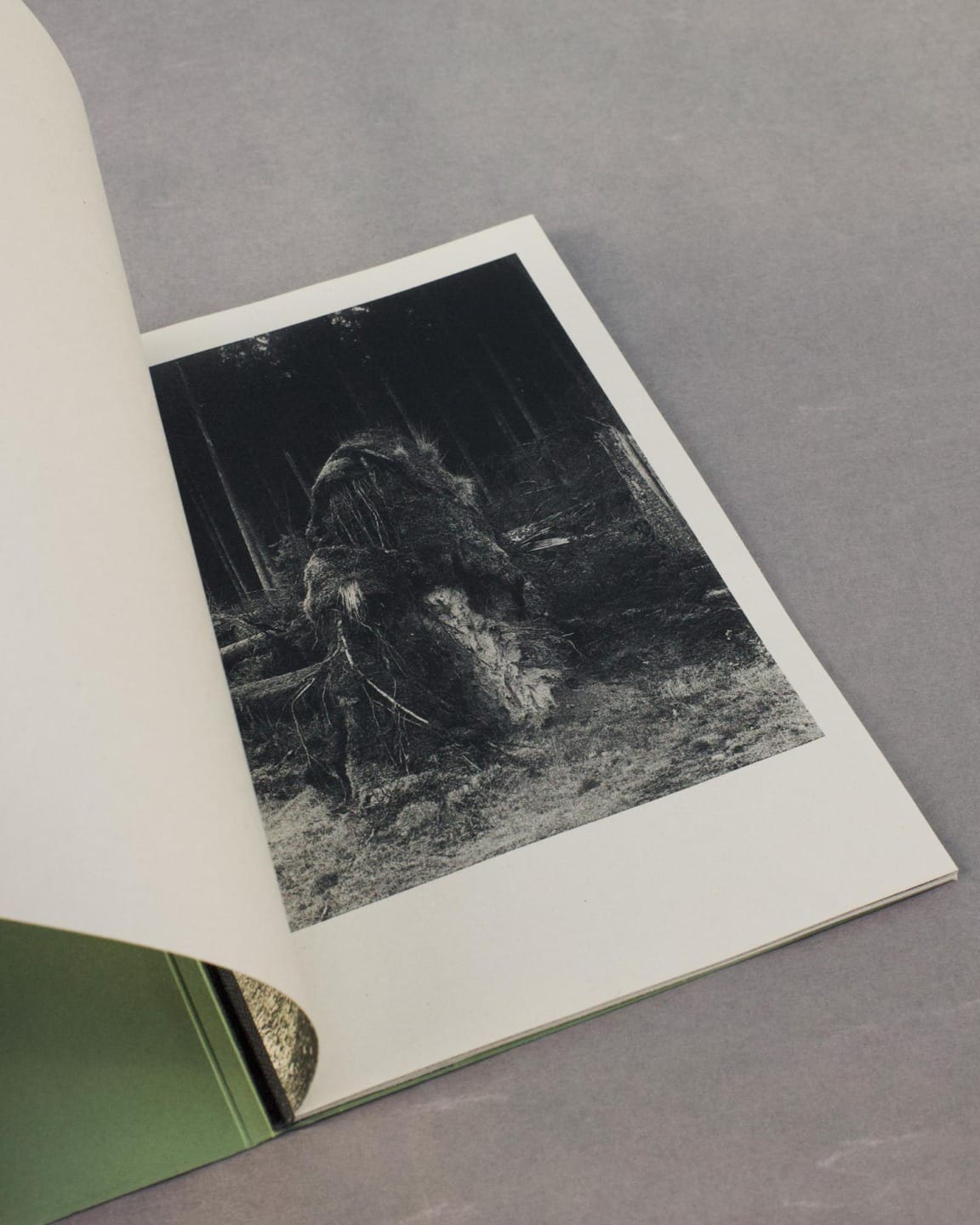

It’s fascinating to me, when out making photographs – I’m often quite aware of how a place feels and I let that guide my process of photographing. Psychogeography!

This was turned up to another level on Dartmoor, because there’s so much history to experience. I think I found it hard to focus on what I wanted to say with this project but I ended up letting the landscape guide that judgment and it became a body of work about that interaction of people and place.

On another note, I’m really fascinated by this crossover of theology, politics and landscape. It’s an odd combination now but it was kind off just how things were back in the day. So that’s something I’m always looking out for and those stone crosses… Well, I don’t think I need to elaborate on that… Wow!

The film accompanying the project includes a reading, in Old English, of your poem Dumnonia – I found it really striking in the way it evoked that strong sense of the past seeping into the present which – for many – is a strong element of the Dartmoor landscape.

Can you tell us a little more about what inspired you to write these words and how you incorporate poetry alongside images in your wider creative practice?

I’m always writing alongside my work as I find it’s a great way to process themes and ideas but this is the first time I’ve made an active choice to make it a part of a project in a physical way. I’m usually against it, I think they both do the same thing, poetry and photography that is, but it felt right to do so here – it was very much part of my understanding of the landscape.

The words actually felt like they were drawn up from the landscape, as if each step I took prompted another letter to rise up through the earth and onto the pages of my notebook. Maybe a little bit of artistic license there, but it did really feel like that at times. I think that poem really just maps out my daily experiences of Dartmoor. I shot the film and photographic body of work over 5 days and each day I was jotting the day’s experience down which became the poem.

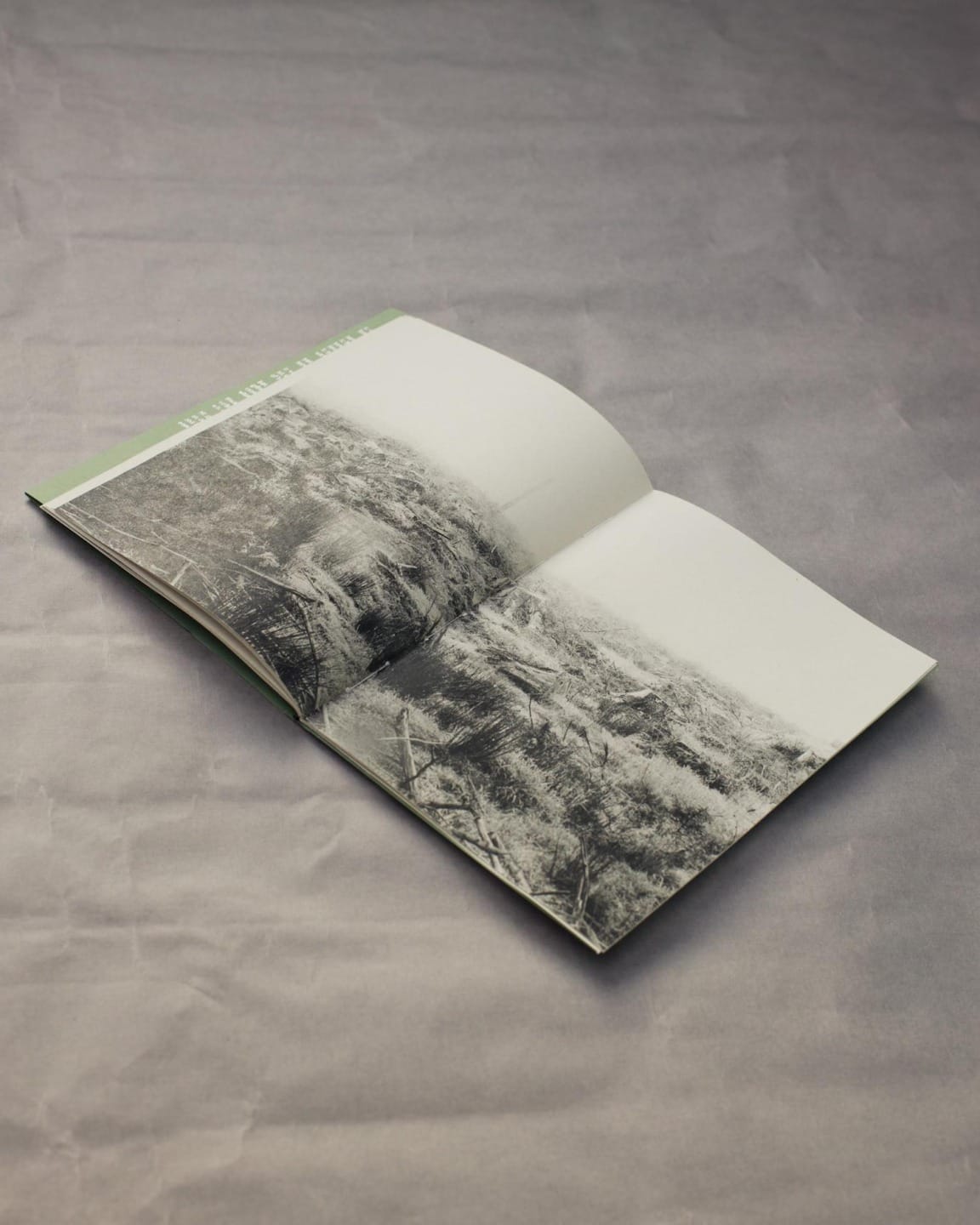

There was a moment as I was walking to the felled plantation at Bellever in the early hours of the morning where I looked across the field up to Bellever Tor and the mist was just sat upon the summit (if you could call it that) and that inspired the line “The mist congeals at the rise” which is one of my favourite lines of that poem. So each part of that poem has a geographical location, I’d be interested to find out what locations come forth when people listen to that poem. Some of the locations in the film don’t match up to the lines spoken over them.

Dartmoor experiences a lot of weather, and much of it is not good – how has that impacted on your technical and creative process in the course of this project?

The not good weather was what I was hoping for, I don’t think I experienced the full onslaught of rain and wind thankfully, as walking around the moor with what is really a wooden 19th century photographic tool wouldn’t have… well lets just say I wouldn’t have lasted long… as much as I like to think I would have persevered. But it was misty with all that mizzle for the entire time and I loved that, it really allowed me to pluck out things in the landscape photographically and direct attention to certain things. So it was actually very helpful.

I think it definitely changed my regular process, usually I can walk towards something with intent, like “oh, there’s a ruin over there that I want to photograph” but it was like a lucky dip most days just waiting to see what would jump out of the mist next. I like that way of working, it feels more intuitive and spontaneous.

Do you see Dumnonia as an evolving body of work and a subject you will return to in some form?

I’d like to think so, I have plans to return to Dartmoor to exhibit some of the work, I’m not sure where… Maybe someone reading this or from Dartmoor Collective can point me in the right direction?

Dumnonia, the Brythonic name for the south-west, technically encompasses Cornwall as well, although some people will say it’s just Devon… but Dumnonia is finished. That isn’t to say I’m done though, I’d like to create some more work on Dartmoor, I just need to find an interesting narrative which I’m sure won’t be hard! There’s so much to draw from, it’s so rich in history, stories and people.

What’s next in terms of future projects?

Well, apart from my plans to return to Dartmoor I do have one thing. I’ve been looking into The Knights Templar, there’s a few organisations a bit more close to home that operate under that name. That’s all I can really say about that now but it’s on my mind….

Copies of Dumnonia are available from Bracken Books.

You can see more of Joe’s work on his website joecharrington.co.uk and on Instagram.