I’m an English teacher by trade, so spend a lot of my time in the world of words and concepts – that’s certainly an enjoyable place to be, but recently I’ve found a tremendous pull towards the usually wordless worlds of photography and drawing. I’m self-taught in both and find the learning process exhilarating. I divide my time between Hampshire (work) and Devon (life), and love to wander around the South Downs, the Exe Estuary and Dartmoor, with camera and sketchbook to hand.

For me, these two modes of image-making are on an equal footing. Camera, pen and pencil have all connected me more intensely and vividly to the world, and seeing the work of expert practitioners in both has provided endless wonder.

As far as drawing is concerned, there are many kinds – from observation, memory, and imagination; figurative and abstract; quick and spontaneous or slow and pondered; light and suggestive or densely detailed – and so on, with a full spectrum of possibilities in between and an array of media to explore. And they speak to each other: imitating a suprematist abstract composition by Malevich can refine your sense of form, space and composition which is something you can then take into a sketch – or a photo – of a tor or cloudscape.

If I have any rule it’s just to keep going and try things out. Risk and experiment seem vital if you are not going to fall into secure formulas, so failures along the way are essential. As Miles Davis said: ‘It’s not about standing still and becoming safe. If anybody wants to keep creating they have to be about change.’

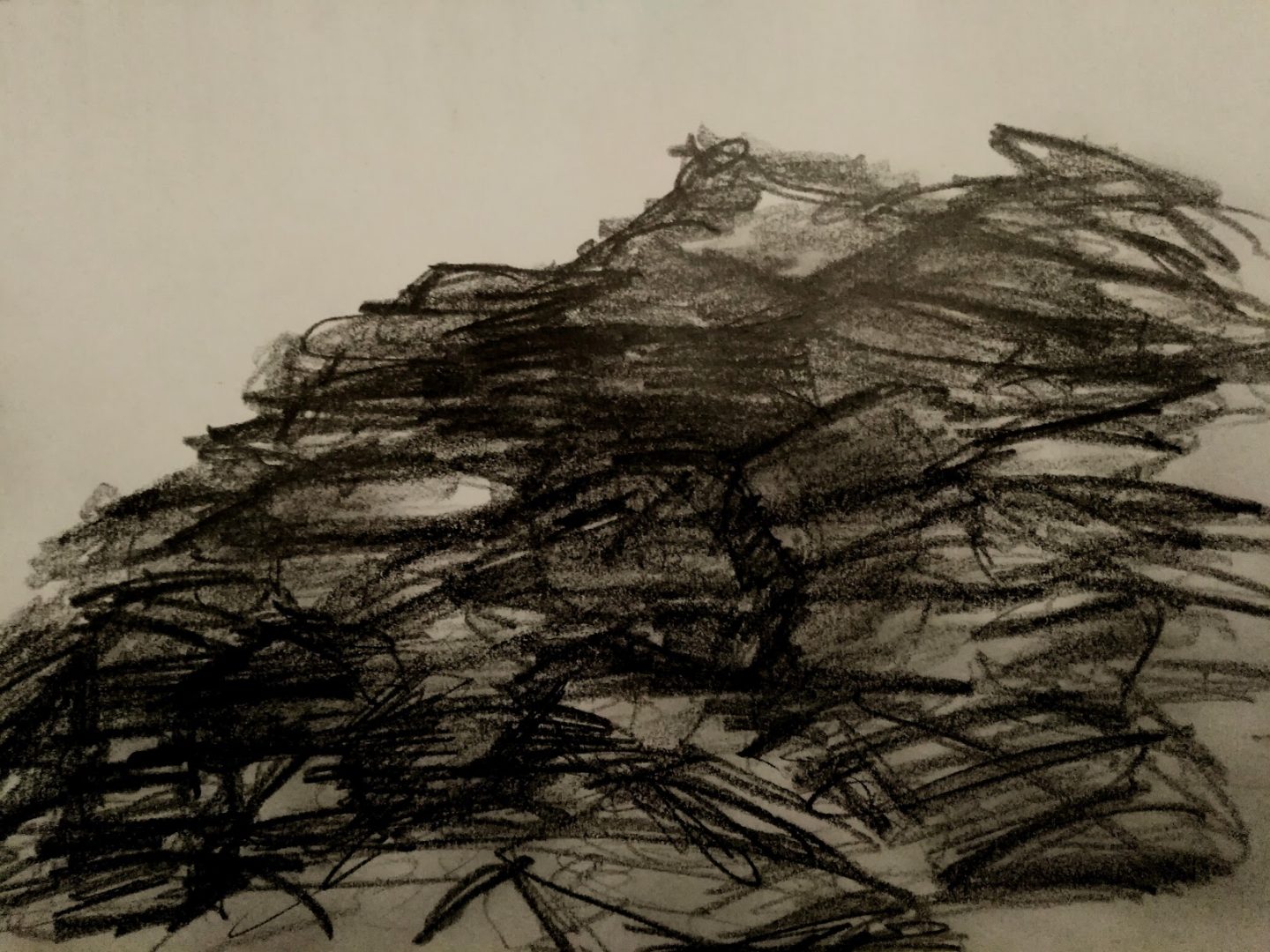

The drawings here are all from a symbolic point of change – New Year’s Eve 2019, when I drove into Dartmoor and did some drawings in the Haytor, Greator Rocks and Hound Tor area. I took some photos, too, purely for reference. Observational drawing like this is something I keep coming back to – the aim is to get down, quickly and without overthinking, the sensation of a scene, looking at the page as little as possible. Squiggles and scribbles have to suggest trees, outcrops, clitter. They are more a response to a landscape than a portrait of one.

I draw in this way chiefly for the experience of the process rather than with the aim of making a masterpiece, but hopefully the final product communicates some of the quality of that experience of being there, in the moment. This kind of on-the-spot drawing is a thrilling exercise in heightened attention, the eye and the hand working together. An important book for me has been Frederick Franck, The Zen of Seeing, a serendipitous find from the Topsham Bookshop.

Some of these images were made in a small A6 notebook, others in an A3 sketchbook, and they were mostly done in charcoal and pencil, with one or two in ink.

Whatever one’s views of post-processing in photography are, it doesn’t help much with plein air sketches. I’ve generally found that fiddling with this sort of work afterwards drains all the life out of it – even correcting an error adds a false note – so I prefer to leave them as they are, in all their squiggliness.

I’m looking forward to being back on the moors, and seeing them differently. No one looking at this website needs to be told by me that Dartmoor is constantly changing, with dramatic alterations of light and texture from one hour to the next, so it’s all there, always new and waiting to be discovered.

Malcolm Hebron

Twitter @HebronMalcolm

Instagram @hebronmalcolm